Operating from a building half the size of a football penalty box, Bygaard mushroom farm is part of the world’s sustainable urban farming revolution.

BY HARPER PESTINGER

Upon thinking of a farm, your mind may conjure up images of rurality, vast expanse and a straw-sucking, hat-clad Old MacDonald-type character.

Bygaard mushroom farm, based on 300 square metres in the outskirts of Copenhagen, is not that. What it might be though, is a sneak peek into the future of agriculture.

Increasingly, the global population is getting its food from space-efficient, hyperlocal farms run with sustainability at front of mind. Copenhagen is no different and, especially given Denmark’s significantly urbanised population, in-city farms like Bygaard are popping up all over.

“Why don’t you just grow the food rurally?”

Squeezing its small population into a few main cities leaves more than 60 percent of Denmark occupied by farmland and agricultural use – an industry which accounts for under one percent of the national GDP.

“It’s very bad business.”

Those are the blunt words of Lasse Antoni Carlsen, founder of Copenhagen’s Bygaard mushroom farm.

Starting off as a team of two in the industrial outskirts of the city, the business came about four years ago and produces eight varieties of mushrooms in six rebuilt shipping containers.

“When we first started talking about it, most people were like, ‘why would you even want to bother doing that?'”, Carlsen tells. “‘Denmark is an agricultural country, why don’t you just grow the food rurally, where there’s a lot of space?'”

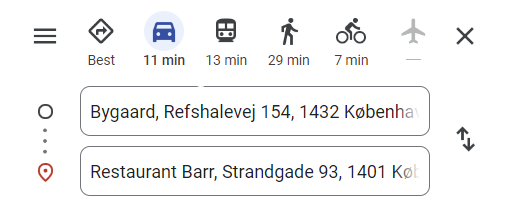

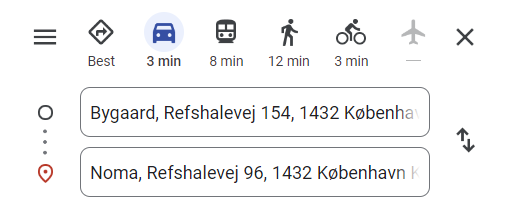

Tightly packed in to capacity, Bygaard now produces 200kg of mushrooms per day that can be bought or enjoyed in every corner of Copenhagen, including the three-Michelin star restaurant Noma.

As Carlsen says, keeping the production “closer to the customers” reduces the otherwise mind-boggling financial and environmental cost of transportation.

Pedalling their goods

When it comes to the production and distribution of oyster mushrooms – part of Bygaard’s stock in trade – 96 percent of the CO2 emissions can be put down to transport and packaging, according to Concito, Denmark’s green think tank. Inherently then, hyperlocal production of food lessens the burden for the planet and wallet alike.

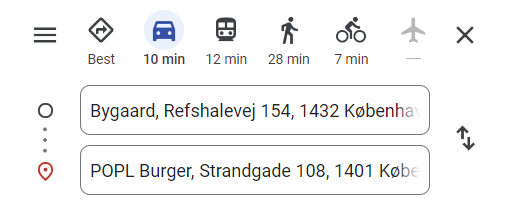

Thanks to both Copenhagen’s pedal-friendly infrastructure and Bygaard’s ethos of sustainability, the business exclusively delivers by bicycle – 50kg per courier.

In addition to that, the mushrooms’ packaging “isn’t really processed”; they’re sent out in cardboard boxes (to restaurants) and wooden crates (to supermarkets).

“We deliver to around 100 restaurants,” Carlsen says. “Chefs send me a text then we have the mushrooms at the kitchen in a couple of hours.”

Mushrooms in and of themselves are one of the least impactful foods produced in Denmark too.

One of the few natural decomposers of wood, the fungi are grown on and eat into sterilised hardwood – sourced by Bygaard as a byproduct from the sawmilling industry. On that hardwood, other residual industry materials – such as sawdust and straw – are weaponised to kill unwanted bacteria.

While Bygaard’s products end up on plates and in bellies, Carlsen says mushrooms can also be used as “building materials” or “styrofoam alternatives”.

Urban farming’s future

“There are fewer and fewer farmers in Denmark, but they’re becoming larger and larger. It’s almost impossible to get a hold on land,” Carlsen points out.

While Bygaard is now undeniably a success story, its founder argues steps need to be taken to ease the initial burden on potential urban farming start-ups.

The standard VAT (value-added tax) across the Danish agricultural product board is 25%, a number Carlsen says needs to be tinkered with.

“In order to make it affordable for the consumer to make the right choices… we should reduce the VAT on organic food to 8% like it is in other comparable countries, then keep it up for the conventional big scale farmers,” he opines.

With a little help from urban farming pioneers around the globe, more and more city slickers might just get the chance to live out their Old MacDonald dreams, right from their bedroom or backyard.

(This story is intended for VICE Media‘s young, international audience)